Marburg Virus – What You Need to Know

If you hear the name Marburg virus, you probably picture a scary disease from a news headline. The truth is the virus is rare, but when it shows up it can be serious. Knowing the basics helps you stay calm and ready.

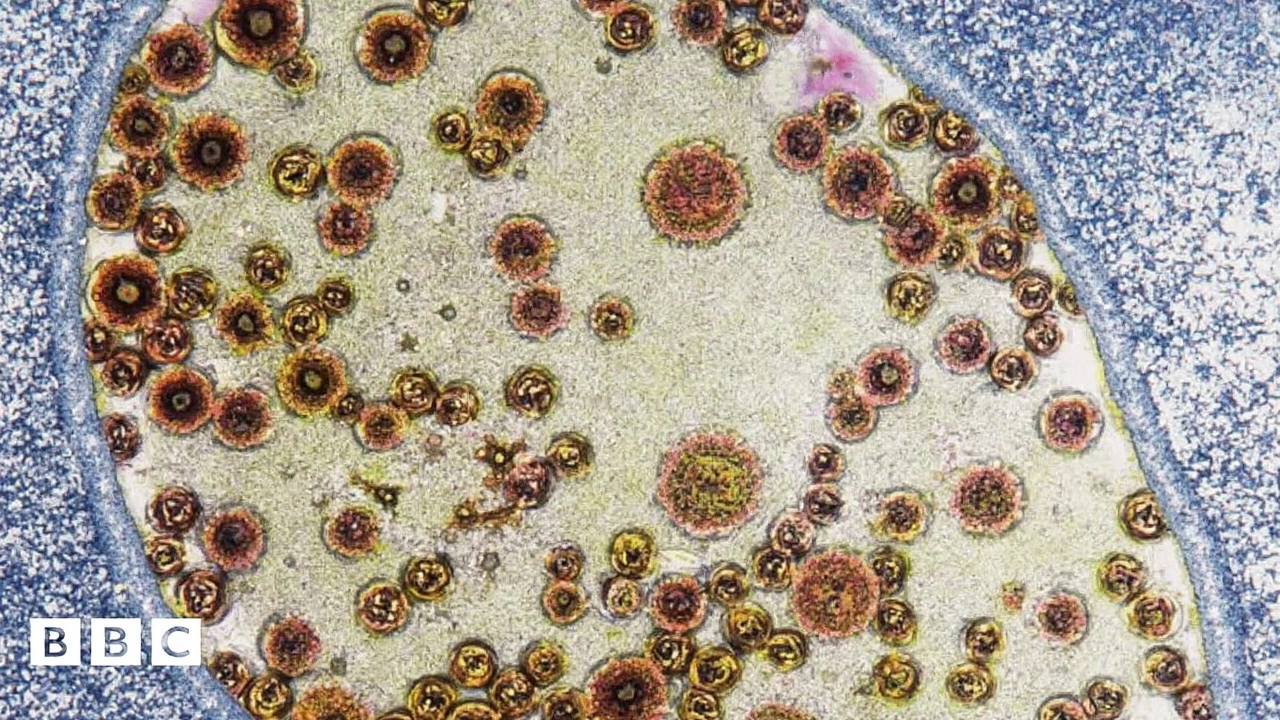

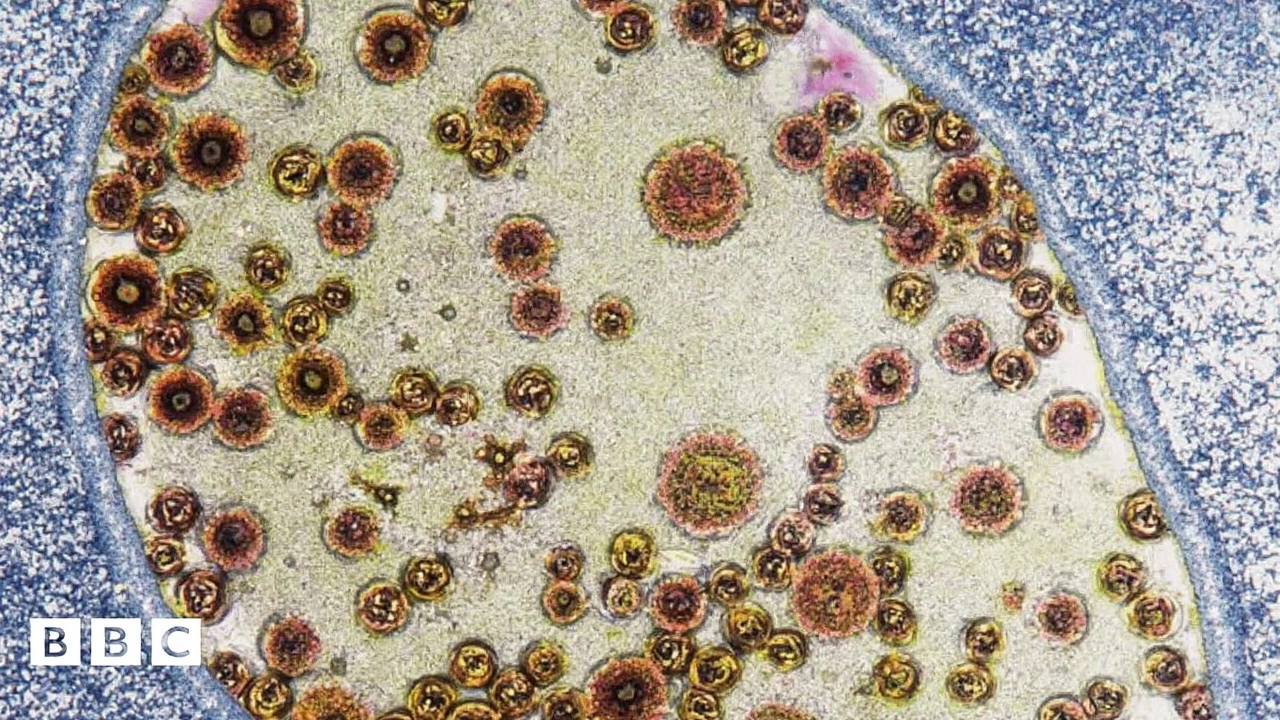

Marburg virus belongs to the same family as Ebola. Both are called filoviruses and cause hemorrhagic fever. The virus was first found in 1967 when lab workers in Marburg, Germany, got sick after handling infected monkeys. Since then, a handful of outbreaks have happened in Africa.

How the virus spreads

The virus jumps to people mainly through direct contact with the blood, body fluids, or tissues of infected animals. Fruit bats are the natural hosts, so touching bat droppings or meat can start an infection. Once a person is sick, the virus spreads easily through contact with their blood, vomit, or stool.

Outside of close contact, the virus does not travel through the air. That means casual conversation or walking past someone won’t infect you. Health workers, family members, and anyone caring for a patient are the highest‑risk groups.

Symptoms and when to get help

Symptoms appear 2‑21 days after exposure. Early signs look like a flu – fever, headache, muscle aches, and weakness. Within a few days you might develop a rash, sore throat, and abdominal pain.

As the disease progresses, bleeding can occur from the gums, eyes, or other sites. Trouble breathing, low blood pressure, and organ failure are possible. If you or someone you know has been in an area with known Marburg cases and shows these signs, seek medical care right away.

Rapid diagnosis comes from blood tests done in a lab with proper safety measures. Early detection improves the chance of survival.

There’s no specific antiviral approved for Marburg yet, but supportive care makes a big difference. Doctors focus on rehydration, maintaining blood pressure, and treating any infections that show up.

Clinical trials are testing experimental treatments and vaccines. Some have shown promise, but they’re still limited to research settings.

Prevention is straightforward: avoid contact with sick animals, especially bats and primates, and wear protective gear if you work in a lab or health‑care setting. Wash hands often, use gloves when handling bodily fluids, and follow strict disinfection protocols.

If you travel to regions where Marburg has appeared, stay updated on local health advisories. Stick to reputable hotels, eat cooked food, and drink bottled water.

Community education helps stop outbreaks fast. When health officials identify a case, they trace contacts, isolate them, and monitor for symptoms. That containment strategy has ended several small outbreaks before they spread.

In short, Marburg virus is rare but dangerous. Knowing how it spreads, spotting the early signs, and practicing good hygiene can keep you safe. Stay informed, and if you think you’ve been exposed, get medical help without delay.

Rwanda faced its first Marburg virus outbreak in late 2024, with health workers among the earliest victims. The virus claimed 15 lives out of 66 cases before authorities, supported by world health agencies, contained the spread through aggressive tracing and infection control, reducing the fatality rate significantly.

Continue Reading