Rwanda Ends Marburg Virus Outbreak After Rapid Public Health Response

Rwanda's Fierce Battle with Marburg Virus

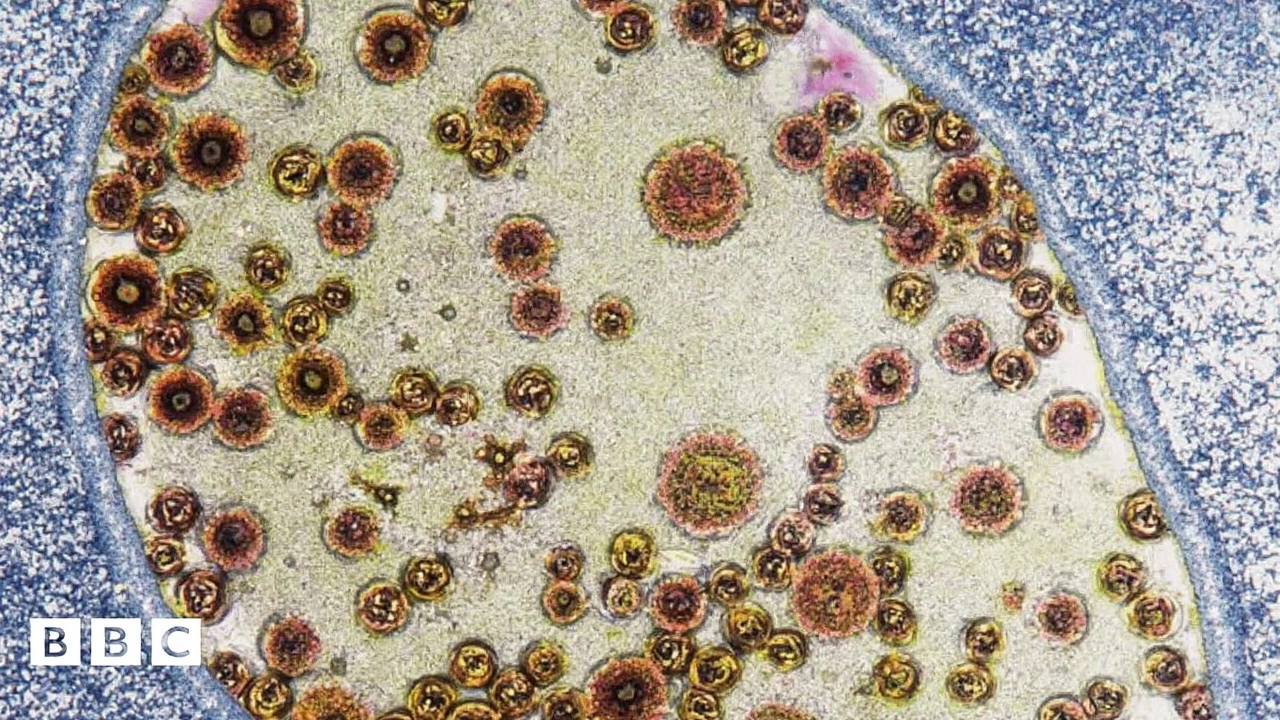

The idea of a deadly virus emerging in a new country is always a shock to the system. In late September 2024, Rwanda reported its first-ever cases of Marburg virus—an Ebola-like disease known for devastating outbreaks and sky-high fatality rates. This wasn’t just a medical story; it was a real-life stress test for Rwanda’s entire health system.

The first confirmed cases came out of Kigali, the capital. The fact that six healthcare workers were among the initial deaths really exposed weak spots in infection prevention and control. When those who are trained to care for the sick fall victim themselves, the sense of urgency ratchets up—the virus had already breached the most basic perimeter defenses.

How Rwanda Responded When It Mattered Most

By December, the stats painted a stark picture: 66 infected across seven districts, with 15 lives lost. But what stands out is how the country, along with partners like the World Health Organization (WHO), European Union, and the UK, rallied fast. They weren’t chasing rumors; they were laser-focused on Marburg virus surveillance, contact tracing, and stopping transmission chains wherever they popped up.

The source was quickly identified as zoonotic—originating in animals, jumping to humans, and then spreading further between people. This kind of early detection made it easier to know where to target resources. Trained teams moved door to door to find and quarantine anyone exposed, while hospitals ramped up infection control.

- Strict isolation protocols kept new suspected cases from slipping through the cracks.

- Contact tracers tracked down nearly everyone who had any contact with patients.

- Daily check-ins became routine for those under monitoring.

- Lab testing scaled up fast, so no one was guessing who was at risk and who wasn’t.

There’s one figure worth highlighting. Historically, Marburg virus can kill up to 85% of its victims. In Rwanda, thanks to improved clinical care and public health management, the expected fatality rate was slashed to just 22.7%. This is a major breakthrough and speaks volumes about the level of detail that went into caring for the sick—supportive fluids, quick diagnosis, and real-time data sharing across clinics all played a part.

After 42 days without any new infections—two incubation cycles—the outbreak was finally declared over on December 20. Rwanda’s Minister of Health, Dr. Sabin Nsanzimana, didn’t mince words about why: the mix of government action, healthcare worker dedication, and international support stopped the crisis in its tracks.

This episode will likely become a case study in how a coordinated response can keep deadly outbreaks from spiraling, even when the odds seem stacked against you.