comet 67P – the icy rock that taught us a lot

If you’ve ever wondered what a comet looks like up close, comet 67P/Churyumov‑Gerasimenko is the best example we have. It’s the same space rock that the European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe landed on in 2014, giving scientists a front‑row seat to an ancient solar system relic. In this guide we’ll break down where 67P comes from, why its shape is so odd, and what the Rosetta mission showed us.

How 67P was discovered

Comet 67P was first spotted in 1969 by two Soviet astronomers, Klim Churyumov and Svetlana Gerasimenko, who were scanning the night sky with a modest telescope. They noticed a fuzzy speck moving against the background stars and logged its position. Over the years, astronomers tracked its orbit and realized it belongs to the “Jupiter family” of comets – short‑period comets that swing close to the Sun every few years.

When 67P comes near the Sun, it heats up, and its icy surface vaporizes, creating that classic comet tail of gas and dust. This process has been happening for billions of years, so the comet is basically a time capsule from the early solar system.

Rosetta’s close‑up mission

ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft was launched in 2004 and spent ten years cruising through space before finally reaching 67P. The highlight was the Philae lander, which touched down on the comet’s surface in November 2014. Even though Philae bounced a few times and ended up in a shadow, it still sent back data that surprised everyone.

One of the biggest findings was that 67P’s shape looks like a rubber duck – two lobes stuck together. This shape tells scientists the comet probably formed from two smaller bodies that gently collided and stuck, rather than being a single smooth chunk of ice.

Rosetta also measured the composition of the gases coming off the comet. It found water with a heavy‑hydrogen signature, meaning the water on 67P is different from Earth’s water – a clue that comets may not have been the main source of Earth’s oceans. The mission also spotted complex organic molecules, hinting that the building blocks of life could be common in space.

Another surprise was the comet’s activity level. Even far from the Sun, 67P was outgassing enough to create a thin atmosphere, showing that comets can be active much earlier than we thought.

For everyday readers, the takeaway is simple: comet 67P isn’t just another rock in space. It’s a window into how the solar system formed and evolves. The Rosetta mission proved that with enough patience and clever engineering, we can study these ancient objects up close.

If you want to keep up with new comet discoveries, follow ESA’s news feed or check out the latest images from the James Webb Space Telescope. Who knows – the next comet might bring even more surprises.

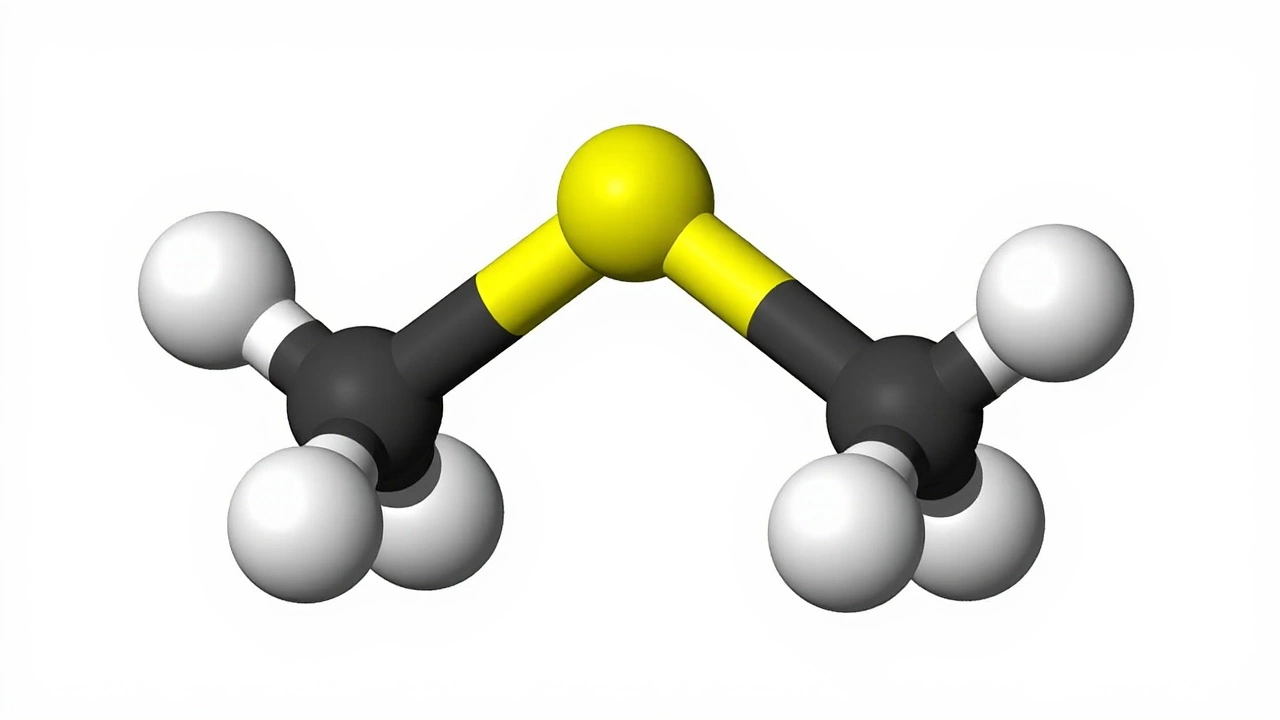

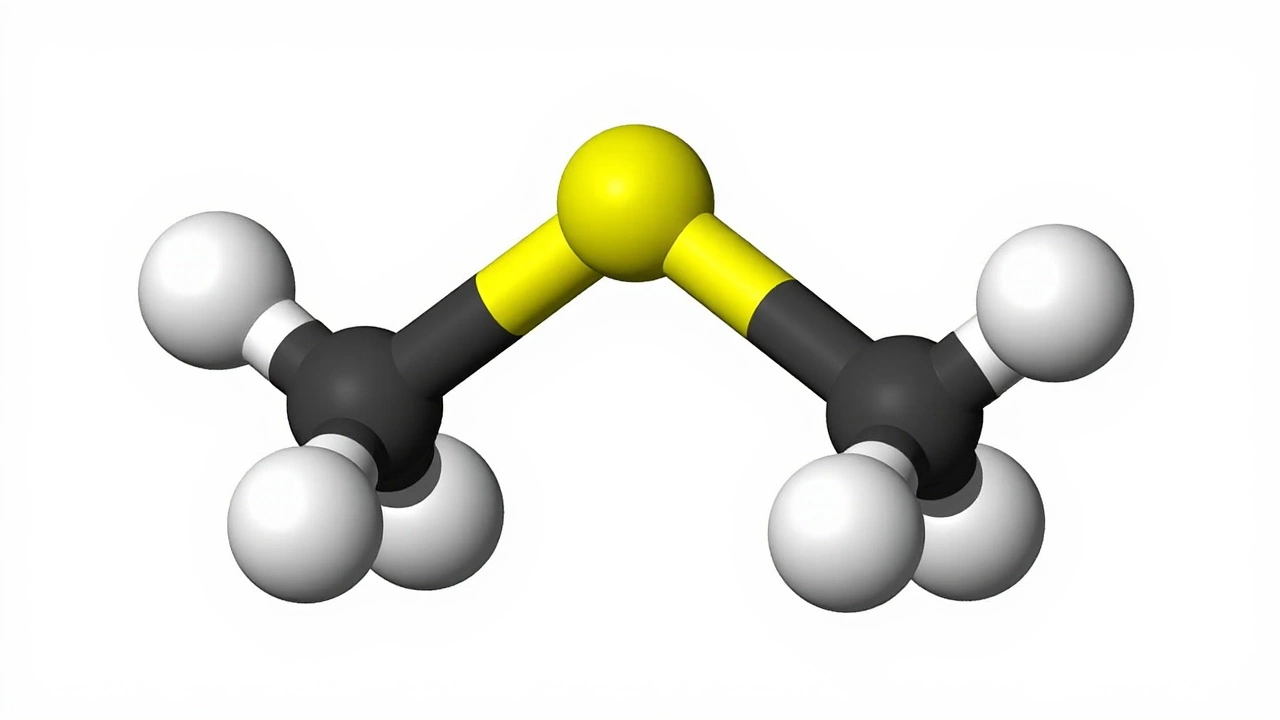

Recent findings by a research team from the University of Bern reveal the presence of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) in comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, challenging its role as a biosignature. Utilizing data from the Rosetta mission, researchers showed that DMS can form through abiotic processes. This discovery, coupled with DMS detection in the interstellar medium, stresses the need for careful evaluation of biosignatures in space.

Continue Reading