King’s Cross Fire: How the 1987 Tragedy Shook London’s Underground Safety Culture

The Night That Changed London’s Underground Forever

If you took the London Underground today, you’d spot emergency exit signs and hear routine safety announcements during your journey. But back on November 18, 1987, those simple details were far from guaranteed. That evening, King’s Cross fire tore through one of the city’s busiest stations, killing 31 people and setting off an overhaul in how the capital viewed transport safety.

It started like an ordinary rush hour. Commuters hurried to catch the Piccadilly Line, tired after work and eager to get home. Just after 7:30 p.m., smoke started drifting up the wooden escalators. Turns out, someone dropped a match — something that would seem small, except these old wooden escalators were basically fuel waiting for a spark. Revolution-era design, little modern fireproofing. The match wriggled under an escalator step, and what should have died out caught instead, slowly roasting the grease and dust that had built up for decades.

Passengers first saw flames flickering below the moving steps and flagged down staff. But here’s the catch: barely anyone on the team had formal fire safety training. The few pieces of specialized fire-fighting gear sat locked away or barely even used. Water fog equipment existed, but without experience or quick access, it might as well have been on another continent.

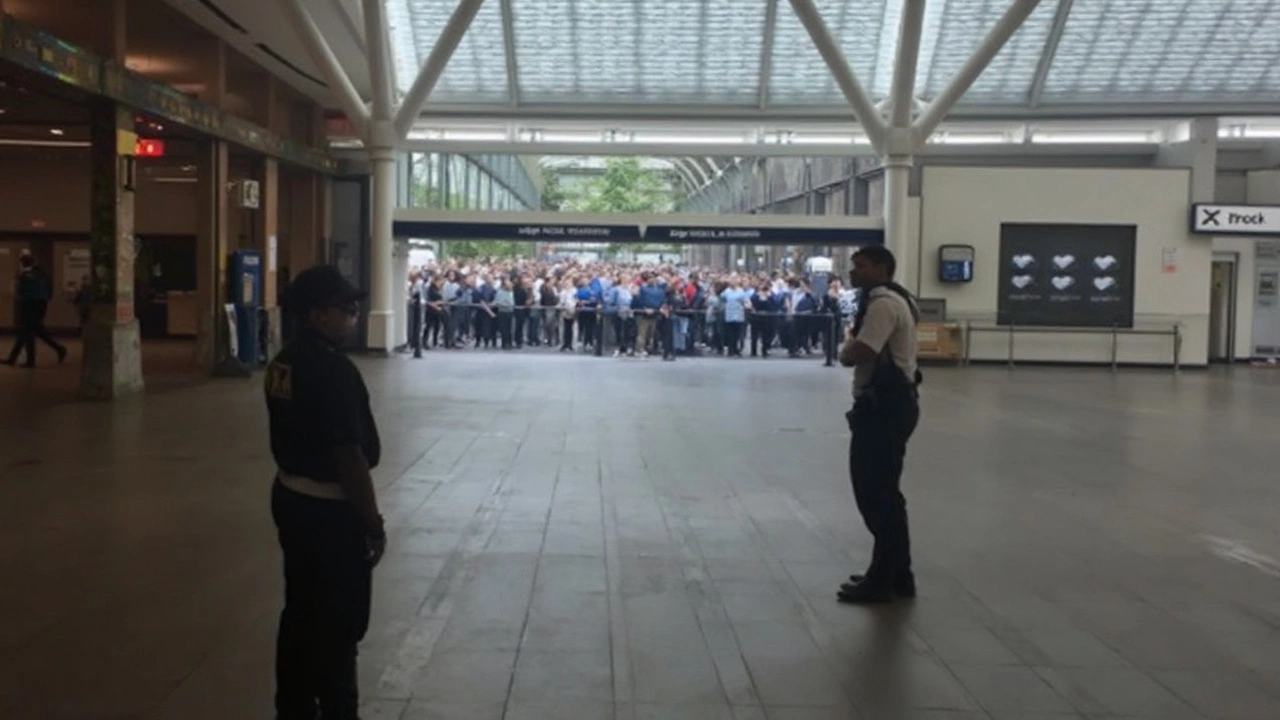

British Transport Police officers and London Fire Brigade crews responded in minutes after the alarm was raised at 7:36 p.m. Still, their efforts slammed straight into the station’s old design. The fire hid deep beneath the escalator where hoses couldn’t reach easily, and smoke slithered through the station’s maze-like structure. Some officers started urgent evacuations through alternative exits like the Victoria Line escalators, trying to funnel hundreds out before things got worse.

When Systems Fail: Lessons From King’s Cross

But "worse" came quickly. Within a short window, a sudden flare — now known as a ‘flashover’ — shot flames and superheated gases up the ticket hall, catching everyone off guard. Fireball-like heat filled the concourse, overwhelming both evacuees and rescue teams. The escape routes everyone trusted weren’t enough. In total, 31 people lost their lives, including a senior firefighter who’d gone back in to help others.

Word of the disaster rushed across London. Televised images of scorched station entrances and emergency crews carrying stretchers haunted the country. But the aftermath brought hard questions: Why was this ancient wooden escalator still in use? Why weren’t staff given proper training? Why did the design allow fire and smoke to climb upwards so quickly, as if the building itself was working against everyone inside?

The answer wasn’t pretty. Much of the Underground’s infrastructure dated back to the 19th and early 20th centuries, which meant regulations and technology lagged decades behind modern expectations. Wooden escalators collected grease and debris like tinder; fire alarms went ignored or misunderstood; smoke ventilation barely worked as intended. The system, designed for comfort and speed, simply hadn’t kept up with the risks of modern crowds or unforeseen emergencies.

Official investigations, led by experts and survivors, discovered the blaze started with that discarded match. But an even bigger culprit was the ‘trench effect’ — a scientific phenomenon where heat funneling up a sloped escalator dramatically accelerates fire growth. No one in the transport industry had studied this properly until the King’s Cross disaster made it impossible to ignore.

The fallout forced sweeping changes. Wooden escalators were ditched for safer metal versions across the entire London Underground. Mandatory fire training became part of the job for every staff member. New smoke detectors, heat sensors, and water mist systems appeared in big Underground stations. The changes didn’t stop at London: cities across the UK and abroad took the King’s Cross tragedy as a warning shot, revamping their own safety regulations overnight.

What happened in 1987 at King’s Cross was more than just a local tragedy. It flipped the entire conversation about transport safety on its head, changing how millions ride underground trains every day. Even decades later, visits to the station remind you — hidden risks shouldn’t be ignored, and sometimes, the biggest change comes from the lessons learned after the worst possible day.